You Could Have Invented Booleans

by Samir Talwar

Thursday, 20 May 2021 at 18:00 CEST

Booleans can be confusing.

Note: The original version of this article used a tweet by David Flanagan, but it’s gone missing, so I have replaced it with this screenshot.

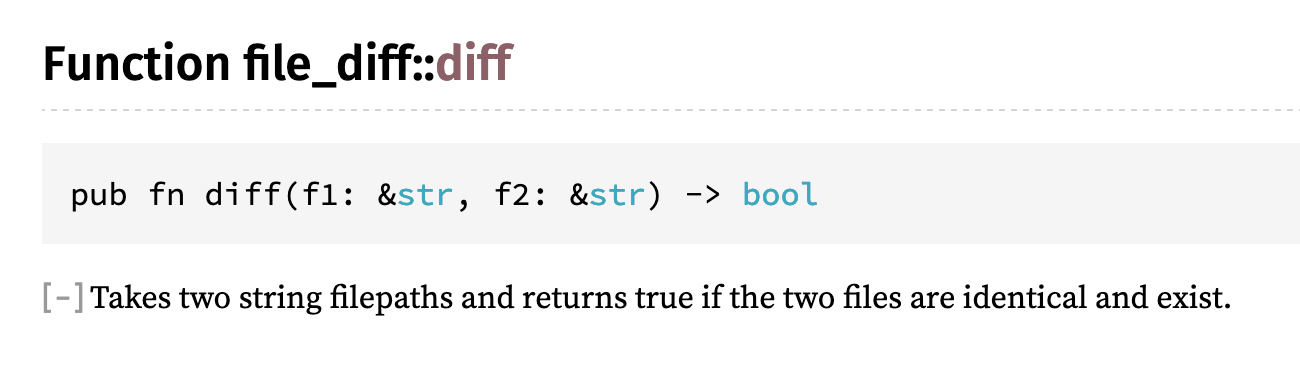

Now, let’s first establish that we’re glad the file_diff crate exists and we appreciate the maintainers for their time. This is not an accusation or criticism of their work, simply an exercise in imagining a different universe where the API of diff is different.

So, with that in mind, let’s imagine we are reading some code that uses diff, and we are confused, because there’ a function called “diff”, short for “different”, that returns true if the two arguments are identical, or not different.

There are a couple of ways we could improve this situation for comprehensibility.

For example, we could change the logic so it returns true when the inputs are different (as implied by the name). That’d work, but then it’d have different behaviour to the diff or git diff programs, which exit with the code 0 (success) when the input files are identical.

Or we could rename the method is_identical (suggested by Stéphane Bjørne). This would make the return value more meaningful, as we can infer from the name what true means.

I’d prefer not to use true and false at all.

Semantically, what are booleans, anyway?

This might seem like a strange question. Truth and falsity, as concepts, are pretty ingrained in us. It’s not just computer people that use boolean logic all the time.

if (it's raining) {

I pick up an umbrella on the way out ☔️

}

if (it's morning || (I'm tired && not (it's bedtime))) {

I make coffee ☕

} else {

I grumble about not having had enough coffee 😫

}

These two examples give us a lot of information about what a boolean is, in terms of what we can do with it. We can “and” (&&) them, “or” (||) them, and not them. (And other stuff, too.) But more importantly, we can if them. We can decide to do something if a boolean is true, and to do something else (or nothing) if the boolean is false.

So booleans are… nothing special.

If that’s what a boolean does, then… we can do that. It’s an enumeration, consisting of false and true.

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum Boolean {

False,

True,

}

(FYI, that #[derive(…)] stuff is just Rust-speak for “implement some boilerplate for me”. This takes care of copying data, equality, and converting to a string for debugging.)

We can implement functionality, such as and:

use Boolean::*;

impl Boolean {

fn and(self, other: Self) -> Self {

match (self, other) {

(True, True) => True,

_ => False,

}

}

}

(I’ll let you implement not and or for yourselves.)

And we can make decisions based on the result:

impl Boolean {

pub fn decide<T>(&self, if_true: impl Fn() -> T, if_false: impl Fn() -> T) -> T {

match self {

False => if_false(),

True => if_true(),

}

}

}

I’ve called this decide to avoid trying to name a function if, which I’m pretty sure wouldn’t make the compiler happy. But modulo some syntax, it’s if in disguise. It accepts functions (impl Fn() -> T is a function that takes no arguments and returns a T) to allow it to only evaluate one clause, not both.

If you’re writing Java, you can do the same thing with subtype polymorphism instead of pattern matching, and an enum:

public enum Bool {

False {

@Override

public Bool and(Bool other) {

return this;

}

@Override

public <T> T decide(Supplier<T> ifTrue, Supplier<T> ifFalse) {

return ifFalse.get();

}

},

True {

@Override

public Bool and(Bool other) {

return other;

}

@Override

public <T> T decide(Supplier<T> ifTrue, Supplier<T> ifFalse) {

return ifTrue.get();

}

};

public abstract Bool and(Bool other);

public abstract <T> T decide(Supplier<T> ifTrue, Supplier<T> ifFalse);

}

It’s verbose, because it’s Java, with the braces and the return or whatnot, but the implementation of and is pretty gorgeous in my opinion. All decision making is done by the dynamic dispatch mechanism, which means we really can implement our own if (or decide, at least).

C# doesn’t have methods in enums, but you can do the same thing with an abstract class, a private constructor, and two implementing classes. (And you can do that in Java too, if you like.)

This is exactly how Smalltalk implements booleans: they’re simply subclasses of the Boolean interface with if methods.

So we can make a boolean.

That’s a very roundabout way of saying that booleans really aren’t core to any language. They’re usually built in so we can wrap some pretty syntax around them in the form of if, && and || (for languages that don’t support operator overloading), etc., and so the compiler authors can optimise operations that have machine code equivalents. The mechanics aside, though, they could be defined in the standard library, or not at all, if we wanted.

Let’s go back to the diff function at the start of this article. Go on, scroll up, remind yourself. I will wait.

So, here’s the code we’re talking about. (Reminder: this is not criticism, and I am assuming the library is pleasant to use and made by lovely people.)

file_diff::diff("./src/lib.rs", "./src/lib.rs"); // returns `true`

Now, we know that a boolean is really just an enum with some syntactic sugar sprinkled on top. This means that we can make our own, and it’s just as valid.

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum DiffResult {

Identical,

Different,

}

Now, bool (and Boolean) and DiffResult are isomorphic: there’s a bidirectional, one-to-one mapping. We can convert DiffResult to bool trivially: result == DiffResult::Identical. And we can convert back, if we really want to:

impl DiffResult {

pub fn from_boolean(b: bool) -> Self {

match b {

false => Self::Different,

true => Self::Identical,

}

}

}

Unlike using a bool, though, our custom type gives us flexibility.

For example, once we have a DiffResult, we might notice that returning DiffResult::Different when one of the input files doesn’t exist seems… odd. And so we might, for example, add a new case: CouldNotReadFile(path: Path). (Yes, enums can have arguments in both Rust and Java.)

Once we have three cases, matching becomes a little more tough, so we might provide a helper method to get back to the boolean value:

impl DiffResult {

pub fn is_identical(&self) -> bool {

match self {

Self::Identical => true,

_ => false,

}

}

}

Now we have a named type, it becomes a behaviour attractor (thanks to Corey Haines book, Understanding the Four Rules of Simple Design, for this terminology). We now have a place to put behaviour that might previously have lived all over the place. This results in less repetition, more consistency (especially among naming), and less work when it comes to refactoring or improving behaviour.

All that said, my favourite side effect of a change such as this is not really related to code, but documentation. By moving away from primitives such as “true” and “false” and towards descriptive terms, we reduce the amount of explanation necessary in the documentation. Indeed, most commentary becomes redundant, as it will end up repeating the code itself. For example, “returns true if the files are identical” becomes “returns Identical if the files are identical”, which is almost unnecessary to say. Especially with statically-typed code such as the Rust shown here, a lot can be inferred just by reading the function signature. (This is not an excuse not to write documentation. Please write documentation.)

You could have invented booleans. But you don’t need them.

If you enjoyed this post, you can subscribe to this blog using Atom.

Maybe you have something to say. You can email me or toot at me. I love feedback. I also love gigantic compliments, so please send those too.

Please feel free to share this on any and all good social networks.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY-4.0).